My Scandi-noir Christmas

You should have seen my tourist-rube face as I stood in Kongens Nytorv for the first time a few weeks back.

I gaped like a 7-year old, transfixed by a baroque skyline etched in Christmas lights, while skaters plowed through rough rink ice at the heart of Copenhagen's 17th-century central square.

Fresh off the metro from the airport, I bumped my wheeled carryon over cobblestones, dodging bundled-up Danes heading into the National Theater for holiday performances of The Nutcracker. I was as awed by the varieties of outerwear as by the extravagant glitter.

Little did I know that Nutcrackers would haunt my weeklong visit to the city, unsettling me at every turn with their unfriendly stares and militant postures. My hotel lobby turned out to be full of them—a couple taller than I am. They looked like they wanted to arrest me, which gave me a dark little shiver.

I had plenty of those shivers as the week wore on.

Copenhagen really Does Christmas, as I had divined that first night on Kongens Nytorv. Even the square's coffee and drinks kiosk, an ornate 1913 "phone booth" that resembles an onion-domed tower out of a fairy tale, was lit up like some fantastical Christmas bauble.

Welcome to Jul on Kongens Nytorv in Copenhagen. Clockwise from top left: Magasin du Nord department store; coffee and drinks kiosk on the square; ice rink with illuminated canine helpers; the blinding dazzle of the Hotel Angleterre, a 1755 Neoclassical palace. Photos: Alison Cook

Copenhagen shops big and small, grand and humble, ground-level and basement-sunken, step up with holiday windows that kept me prowling the avenues like some restless ghost. I was drawn in not so much by the sparkle nor the folksiness nor the sentiment, but by the dark undertow I sensed in my Scandinavian bones.

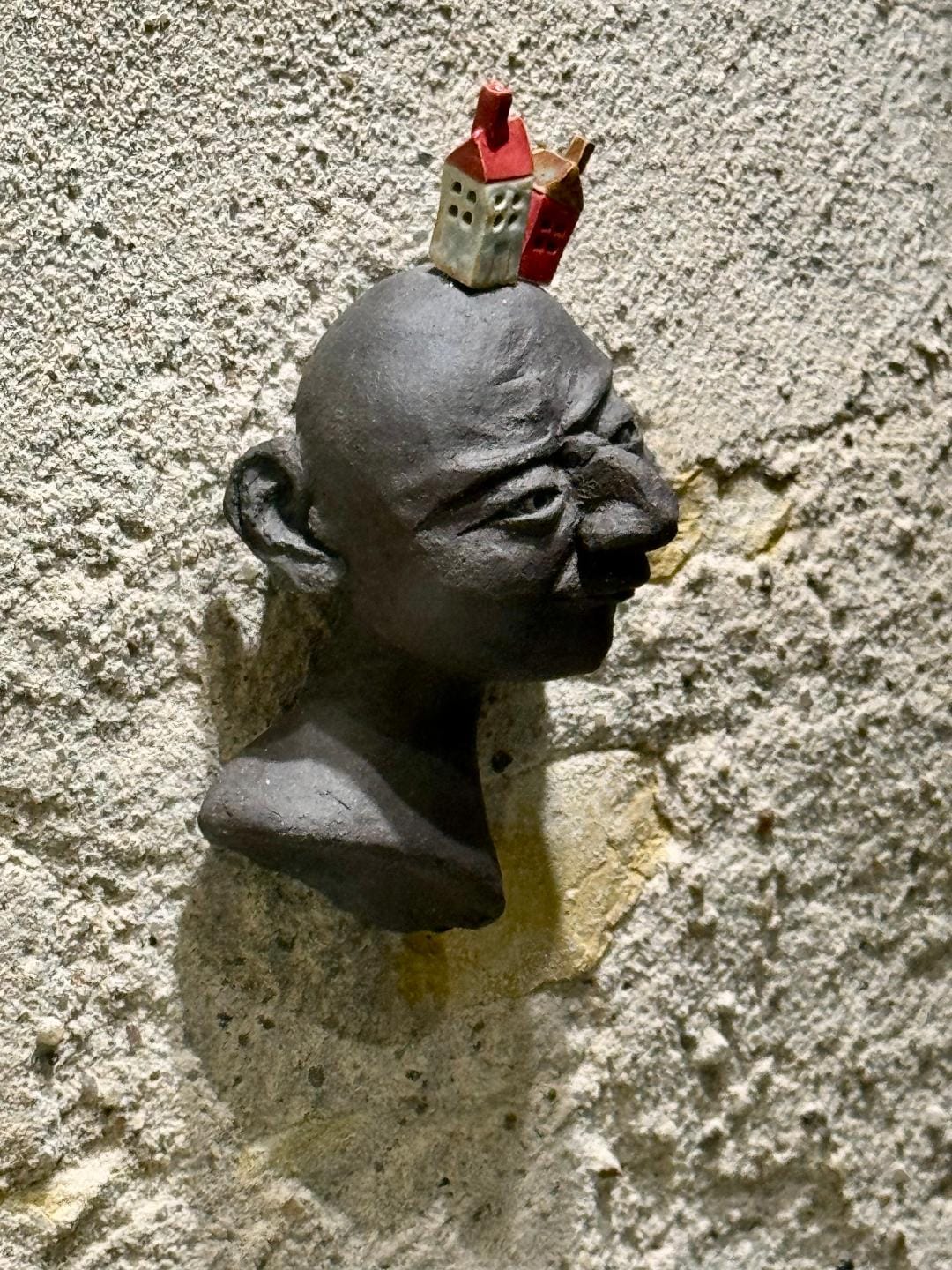

Something wild and raw and a little pagan animated many of the displays. Something that spoke of perilous forests, dripping with moss and lichens and clawing bare branches, populated by sprites whose intentions I found questionable.

I had always been a little unnerved when my Swedish mother broke out the Christmas tomtegubbar ornaments. The red-hatted, long-bearded elves are said to lurk in Swedish houses and farmyards. Ostensibly they are there to protect. But the lore says the tomte is an easily offended sprite who can make you sorry you pissed him off. As a breed, they're inscrutable and--like the nutcrackers--a little menacing, with their tall, pointy hats pulled down over their eyes, so only their noses stick out.

Tomtegubbar were everywhere in Copenhagen, in window-display settings both glittering and rustic, opulent and severe. So were woodland vignettes with a wild, dangerous edge. After an eight-mile prowl up and down the shopping streets of the central city, I emailed my sister in excitement. "These are our people!" I told her. "They do a trollish dark fairy tale vibe as second nature."

Once I began emailing her my photos of Copenhagen's Jul windows, I couldn't stop. Our mutual fascination with miniatures springs in part from the childhood Christmas villages that sat at the foot of our tree, inhabited by various critters on skis or sleds, dressed for the season. Now here those animals were again, in every other window, dressed in nightshirts and caps or perched on holiday ceramics. When shiny ornaments appeared, they were often vintage stuff, summoning up Christmases long past, their muted sheen ever so gently mournful.

There was nothing sappy about the Christmas displays at which I lingered longest. They hearkened back to the holiday's pagan roots in the winter solstice. Jul, or Yule—the season which extends from Advent through Epiphany—stems from ancient Norse midwinter festivals celebrating the return of light. That origin was still palpable in the streets of the city.

Copenhagen Jul windows that look like they were made by wild elves: a woodland snarl; a mysterious creature; an antique store's skulls and medical displays amid gold ribbon and pine cones; goblets arranged by more wild elves. Photos: Alison Cook

I felt the approaching solstice in my chilly Houston bones during that first week of December. The days seemed astonishingly short. I arose each morning at 8 a.m. to watch Danes trudging to.work in the dark under my window. At 3 p.m., night started drawing in again, so that by four the skies were black.

Tivoli Gardens, that fantastical amusement park that I had once visited in summer, now stood out against the dark as one big, multifaceted holiday ornament—a faux cityscape of light-limned towers and high, whirling rides. I stood beneath one of them and marveled at the screams drifting down to street level.

For the first time, I understood viscerally why Christmas candles are important in Scandinavian culture. They represent light in the wintertime darkness, with its raw, primitive edge. My mother always perched electrical candles in each window of our house during the holidays. For the first time, I got it.

So much so that at the domed and turreted Magasin du Nord department store, its twinkling lights etching the skyline above Kongens Nytorv, I found the 21st-century equivalent of our family's midcentury electric candles. These were longer, more elegantly tapered, made of some miraculously strong paraffin.

Their LED flames flickered like real candles. One now sits in each of my Houston bedroom windows, protecting me through our dark, warm winter nights.

A vining thicket of antique Christmas ornaments; Tivoli Gardens at night; critters in a stylized holiday forest; critters doing Jul things; the Nordic Jul tree at is most elemental, at Vyn Restaurant on the southeast coast of Sweden; life-size disapproving nutcrackers in Copenhagen's Phoenix Hotel. Photos: Alison Cook

Member discussion